100 SUNSETS BY ZACH LIEBERMAN

This was part of an ongoing series of articles that released was digitally in November 2022. They were first published in the print edition of the Bright Moments Quarterly that was distributed at NFT ART CDMX in Mexico City.

Malte Rauch: Your career started around the year 2000 – in an environment that people have come to describe as Web1. In the twenty years since then, you have established yourself as one of the most widely recognized media artists. Now you are active in the NFT space as well. How did you experience the development of your work as an artist from Web1 to Web3?

Zach Lieberman: I got into design during the 2000s. And I really fell in love with the Flash community, whose energy was quite infectious at the time. Prior to that, I didn’t really know how you could use a computer for making animations. But I saw many parallels between the Flash community and the printmaking world, which is where I came from in terms of my education. The social aspect of sharing code on the internet reminded me of how we would share tips and advice in the printmaking studio.

Back then, it was hard to find inspiring resources about programming. Most of the books were horrible. They were all focused on “how” – books like, “Learn Java in 21 Days.” I distinctly remember being in the book store and running through the computer aisle feeling frustrated when I discovered John Maeda’s Design by Numbers, which really stood out since it focused on “why.” The book explored computers as their own medium. The book was immensely influential for my work and it opened my eyes to the poetic potential of computation.

In the two decades since then, my work was less influenced by the development of the internet (although the different communities and the different opportunities for sharing your work were important) and more by the availability of new tools.

You regularly post new works on social media. What is your daily creative practice like? Is the interaction with the audience via social media important for you?

As an artist, you always have a lot of self-doubt – voices in the back of your head which say, “this isn’t good enough.” And that can really stifle your creativity. For me, the idea of creating and sharing is like a muscle. Ideally, there should be no friction between creating and sharing the work. Doing daily sketches is like a public diary. It is a way of living with the work. And I like being in constant dialogue with my audience. That being said, if you put out a lot of work, it’s important that you keep your focus on your own intuitions. You can’t get addicted to likes and engagement metrics. It’s a delicate balance. You have to be able to stay true to yourself regardless of the reactions.

Apart from your work as an artist, you are very active as a teacher. You are a professor, the founder of The School for Poetic Computation, and for a long time you have offered open office hours. What is your approach to teaching digital art?

There are three parts to my creative practice: art work, commercial work, and teaching. I like the three fields and I find having the right balance is very important. Working in each of these fields is mutually enriching. Teaching has been important for me because it keeps me in contact with the next generation. You know, I have been doing this for a long time – and if you do something for more than two decades, there is always the danger that you get bored, thinking that you have seen it all. Teaching young people keeps the practice alive. You feel their excitement and that is immensely inspiring. For me, it’s a process of giving and receiving. I think that I can convey a lot of knowledge to my students; but I mostly feel grateful to be in contact with their excitement about digital art.

That’s fascinating. Do you have the feeling that the popularity of NFTs have changed the students’ attitude towards generative art over the last two years?

My students are certainly aware of what’s going on, but I would say that they are interested in the art regardless of the distribution technology. What drives my students – and this has always been the case – is the fascination with computation and graphics. “How can we use code in a creative and expressive way?” That’s how I would describe the main motivation.

That being said, it is of course great to see that the rise of NFTs allows artists to create more freely. It will allow students to monetize their practice in a way that was simply not available previously.

How do you find new inspiration for your work (apart from your work as a teacher)?

For me, inspiration is always about finding other artists and having a conversation with them. In teaching, I try to let my students find artists who speak to them and with whom they can engage creatively. And in my practice, it’s the same: I find artists, I research their work and read everything about them as well as everything that they’ve written. I try to get a little lost in their world. And if I don’t know what I should do with my own work on certain days, I always return to the work of classics like Vera Molnár and Manfred Mohr. Going back to their work and immersing myself in it is a constant source of inspiration for me.

Let’s pivot to your work for NFT ART CDMX. You have a lot of experience with exhibition design and many of your shows have an interactive component. One could think of the idea of IRL minting as a new type of interactivity. How do you approach the idea?

Yes, I think there is something quite beautiful in seeing an artwork emerge. Giving the process of minting a special place is interesting from the perspective of exhibition design and interaction as well. And there is another aspect that I find intriguing: the idea of trying to capture a moment. Collecting a work of art is something quite joyful. This is what live minting allows for.

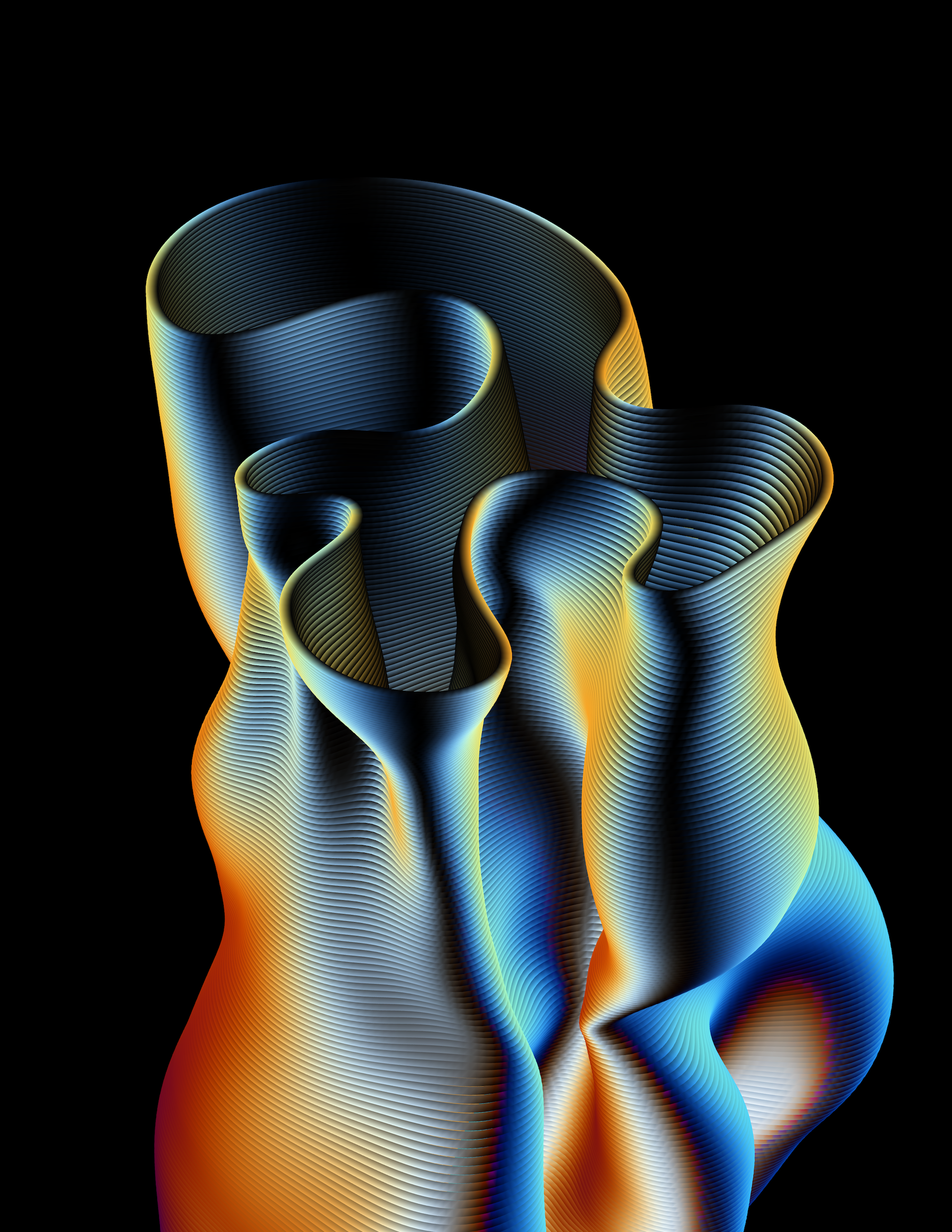

The work you have chosen is titled “100 Sunsets.” Explain how the work has evolved and why you chose this specific project for the event?

When I was an art student, I lived in the Netherlands for some time. And I remember a student who would always run up a hill or climb a tree to see the sunset. Each day, whenever the sun began to set, he would run off to find a spot to watch it… This attraction to the sunset impressed me, and the memory of it has always stayed with me – maybe because I can relate to it on some level.

In each sunset, there is this pure delight of color. When you take a moment to watch the sunset, you have this pure joy of seeing the interplay of changing colors. To be clear, I really don’t like to create representational art, and my project is certainly not about representing a sunset through code. But my work is very much concerned with light, color and gradients. And I want to study sunsets from that specific angle. What do sunsets feel like? How can I convey that feeling?

In general, I think that art is often in a dialogue with nature. Again, it’s important not to misunderstand this in representational terms. Art is not always about making images of nature (although some artists do a really great job of that). Rather, I think it can be more about seeing and understanding nature in specific ways. If we take the sunset as an example, I would say that it is about the emotional connection to the phenomenon, which appears to be a universal feeling. Sometimes, there are these moments where everyone just stops and looks at the sun setting and thinks about the day ending. What does that moment feel like? Can we hang out there and explore it through code?

That’s fascinating. Could you elaborate on the non-representational dialogue between nature and generative art in particular?

Each medium has a unique style. All mediums have a grain or a structure that defines them. When I think of digital art, I think of the pixel, of glitches, and repetition. So on that level there is not that much in digital art that would remind you of nature – compared to say, carving a piece of wood to make a sculpture.

But in a more indirect sense, natural and artistic phenomena communicate, in my opinion. A couple of months ago, I was living on a boat for a week. And I spent a lot of time studying the light reflections on water. The way light and color play on the water surface is – somehow – very reminiscent of playing around with a noise algorithm. We get into an area that is quite hard to articulate properly, but a lot of generative art seems to communicate with these natural phenomena on an aesthetic level. I think we are often trying to articulate in code the distilled essence of what those moments feel like.

I am inspired by the idea that poetry – in a very broad sense of the term – discloses a different view of natural phenomena, one where nature does not appear as something that can be used and exploited. Given that technology is generally quite purpose-driven, there is something very meaningful about reclaiming this poetic element in computation.

The NFT hype of the last two years has changed the field of digital art and in particular generative art. Where do you see the space headed in the future?

Despite the fact that I have been involved with digital art for some time, I am not sure whether I am in a particularly good place to evaluate where things are headed. But it is an interesting moment for generative art because it has always been so hard to collect this work. And in the end, as an artist you always want to find a home for your art – be it a festival, a museum wall, or someone's home. And this aspect of stewardship has been really revolutionized through blockchain technology.

You know, I remember a night with the head of Ars Electronica in Japan around 10 years ago. We were drinking Sake late at night. And he told me: “Your generation will suffer because this work is so damn hard to preserve. But there will be a moment when digital art can be stored in an adequate way.” I kind of laughed it off at the time and was like, what is the old guy on about. But when I minted my first work on Ethereum, it felt really meaningful to say, “I want to record this” and I had to think back to that moment in Japan. It’s hard to overestimate what NFTs have achieved for generative art in this regard.

And even though I just said that I am not good at predicting what’s going to happen next, I would lean myself out of the window with one prediction. We have reached a point where people want to live with the generative art they purchase. The innovation we have seen for preserving digital assets is yet to come for their display. People want to live with this work. And that’s why I think that new forms of high-quality displays are inevitable.

Lastly, I would like to get your take on the new AI tools, which have made so many headlines recently. You have observed the development of many digital tools. What do you think of the new image synthesis models?

The whole development is quite interesting. And, to be honest, I think I have a mixed opinion. On one level, it is super exciting that we can generate images in this new way. There is something radically new about it, and part of me feels attracted to that. On another level, I am quite nervous because, ultimately, this is really about automation. The technology does raise serious questions about the role of designers and illustrators in the future. So I feel conflicted; I am torn between anxiety and excitement.

One thing I’m confident about is that the work with these tools shouldn’t just stop at the output. The relationship of art with tech is always a dance. And you have to make sure that tech is not leading the dance. Are we making artwork in service of technology or using technology in service of art? We should be making poems not demos – this is what I always say to my students. And it applies to the AI image tools as well. How can we make poetry with these tools? That’s the most important question, in my opinion. Going forward, my hope is that these tools will change but not replace the job of making images. That would be exciting to watch.